The digestive system plays a critical role in breaking down large food molecules into smaller readily absorbable units. This animated video details how food is processed as it moves through the digestive system.

Transcript

Chewing breaks down food particles and mixes them with saliva.

Saliva contains the starch-digesting enzyme amylase and a slippery protein called mucin that helps to lubricate the food particles for easier swallowing.

As food is swallowed, it enters the oesophagus and is moved downwards by wavelike muscular contractions called peristalsis. At the end of the oesophagus, the food empties into the upper portion of the stomach.

The lining of the stomach produces gastric juices that contain protein-digesting enzymes. Peristaltic movements of the stomach wall mix and churn the food with the gastric juices. This action further breaks up the food particles, forming a milky fluid known as chyme.

At the bottom of the stomach, a muscular valve controls the release of chyme into the first part of the small intestine called the duodenum. The duodenum is only 25 cm long, but most of the digestion takes place in this region.

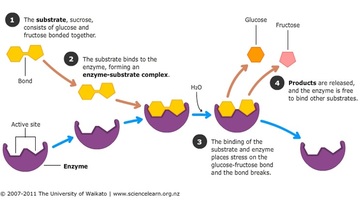

Also opening into the duodenum are ducts from the pancreas and the gall bladder. These allow enzyme-rich pancreatic juice and bile to be released and mixed with the chyme. Chemical breakdown of carbohydrate, protein and fats into smaller absorbable molecules takes place.

The next section of the small intestine is the jejunum, about 2.5 m long. Folds in the wall of the jejunum greatly increase its surface area, allowing for ready absorption of the products of digestion.

The inside of the jejunum and ileum are lined with tiny finger-like projections called villi. These increase the surface area of the small intestine. They play an important role in absorbing the breakdown products of digestion.

Each villus has a rich blood supply, allowing nutrients to be readily absorbed and transported to the liver. Also present is a system of vessels known as a lacteal, which absorbs fat nutrients and carries them to the circulatory system.

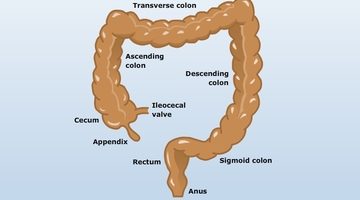

At the end of the ileum, a muscular structure controls the release of undigested material into the first part of the large intestine – the caecum.

From here, peristaltic movements push the undigested material down the large intestine and allow it to mix with the large bacterial population present.

The bacteria are able to ferment some of the undigested material, producing short-chain fatty acids. These are used as an energy source for the bacteria and the cells lining the large intestine. Other important chemical compounds such as vitamin K are also produced by this bacterial action. As the material slowly moves down, undigested material is compacted and absorption of water and electrolytes takes place.

Undigested and compacted material enters the rectum for temporary storage before being eliminated through the anus.