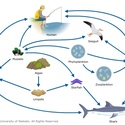

Research into food webs has come a long way in the past 50 years. The view of simple linear food chains where small fish are eaten by bigger fish has been replaced by a much better understanding of the complexity of food webs.

Research has shown that, instead of simple linear chains, food webs are networks of interactions between large numbers of species1. Some of these interactions have even been shown to cross boundaries between land and sea.

Dr Stephen Wing is an associate professor in the Marine Science Department at the University of Otago. He works with a number of colleagues and postgraduate2 students exploring food web structure in Fiordland. Together, they investigate ‘what eats what’ and study primary producers, such as phytoplankton3. One of the main aims of their research is to learn more about the interactions between marine organisms and human impacts on food webs, so we can take better care of the fiords4.

The role of cockles in the food web

Over the past couple of years, the New Zealand cockle (Austrovenus stutchburyi) has been a focus of much of Steve’s research. Cockles play a very important role in the marine food web. They feed on particulate matter5 from the primary producers, such as phytoplankton. Larger animals like crabs and fish then eat cockles. Crabs and fish are eaten by larger fish and sea birds, and so on.

Removing cockles from the food web removes an important link between primary producers and the smaller carnivores6, which, in turn, affects the rest of the web. Cockles also provide another important food web service – they help prevent blooms of phytoplankton that reduce oxygen7 availability for fish and many other species.

Nature of science

Scientists sometimes use anecdotal evidence8 as a starting point for their work. By developing a research plan and investigating matters in a scientific way, they are able to produce evidence to offer reliable explanations for things that happen. The scientists often compare their results with results of other scientists to verify whether their results are a realistic indication of what is actually happening.

Changes in salinity – the impact on cockles

In Doubtful Sound, a hydroelectric power plant releases large volumes of freshwater from Lake Manapōuri into one of the coves. Steve and his colleagues wanted to investigate whether this freshwater input was affecting cockle populations9 and the rest of the food web in Deep Cove.

Anecdotal evidence suggested that the number of cockle beds in Deep Cove had reduced. Steve and his colleagues devised a research plan to investigate the issue scientifically.

They began by looking at the chemistry of the cockles’ shells in Deep Cove. They used chemical markers10 in the shells to determine the salinity11 conditions12 in the cove before the power plant was built. This study showed that water in the cove had previously been more saline – the environment preferred by cockles.

The next step was to carry out a population13 survey. Steve and his team surveyed cockle beds in Deep Cove, other coves in Doubtful Sound and in neighbouring fiords. From this information, they worked out that the cockle populations in Deep Cove are lower than expected, based on data14 from similar areas nearby.

The final part of the study looked at the impact of reduced cockle populations on the food web in Deep Cove. The results showed that consumers, such as rock lobsters, that typically rely on cockles and other bivalves15 had changed their diet and started feeding on a species of small clam. This is significant because this clam obtains all of its energy from bacteria16 that are chemoautotrophs. The bacterial energy source is smaller than the one provided by the primary producers. As a result, there is less energy to support rock lobsters in Deep Cove.

Using science to manage natural resources

These results allowed Steve to predict that removing cockles from a food web can have dramatic results. His research supports information from other places around the world where the removal or reduction of cockles or other bivalves has had effects all the way up the food web. This knowledge has important applications for natural resource management17.

For example, in Fiordland one of the aims of understanding the food web better is to inform policy. Some of the earlier research carried out by Steve and his colleagues contributed to the establishment of Fiordland’s marine reserves in 2005. These reserves minimise human impact on the fragile flora18 and fauna19 in the fiords and are an important tool in marine conservation20.

Useful links

Professor Stephen Wing is the Project Leader on a research project 'Forensic Food Webs' for the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge. The project is looking at ecosystem21 connectivity to inform ecosystem based management.

Find out more about Fiordland’s marine reserves on the Department of Conservation website.

- species: (Abbreviation sp. or spp.) A division used in the Linnean system of classification or taxonomy. A group of living organisms that can interbreed to produce viable offspring.

- postgraduate: A student who has obtained a first degree and is now working towards a higher degree such as master’s or PhD.

- phytoplankton: Very small plant organisms that drift with water currents and, like land plants, use carbon dioxide, release oxygen and convert minerals to a form animals can use.

- fiords: Narrow inlet of sea, normally surrounded by steep landscapes. Typically created by glacial action.

- particulates: Extremely small solid particles suspended in a gas or liquid, for example, soot or dust suspended in the air.

- carnivores: Animals that eat other animals.

- oxygen: A non-metal – symbol O, atomic number 8. Oxygen is a gas found in the air. It is needed for aerobic cellular respiration in cells.

- evidence: Data, or information, used to prove or disprove something.

- population: In biology, a population is a group of organisms of a species that live in the same place at a same time and that can interbreed.

- chemical marker: In ecology, something in the chemical composition of an organism that can tell us something about the environmental conditions, i.e. food availability or water chemistry during the life of an organism. Sometimes they also called chemical ‘fingerprints’ or ‘signatures’.

- salinity: The amount of chemicals dissolved in water. In seawater, the main chemical is sodium chloride (salt), but there are many others in smaller quantities.

- condition: An existing state or situation; a mode or state of being.

- population: In biology, a population is a group of organisms of a species that live in the same place at a same time and that can interbreed.

- data: The unprocessed information we analyse to gain knowledge.

- bivalve: 1. Any mollusk, of the class Bivalvia, which has a soft body within two hinged-shells. Examples include mussels, oysters and scallops. 2. Having two similar parts hinged together.

- bacteria: (Singular: bacterium) Single-celled microorganisms that have no nucleus.

- resource management: Managing human impact on the environment in a way that is sustainable.

- flora: A flora (with a small f) refers to the plant life occurring in a particular region. A Flora (with a capital F) refers to a book or other work that describes and identifies a flora.

- fauna: Animals.

- conservation: The protection, preservation and careful management of a species, habitat, artifact or taonga.

- ecosystem: An interacting system including the biological, physical, and chemical relationships between a community of organisms and the environment they live in.