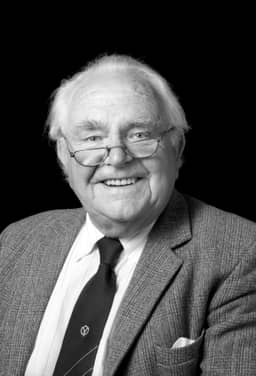

Thomas William Walker – soil scientist

Thomas William Walker – soil scientist

- Changing scientific ideas

- Advances in science and technology

- Biography

- 500 BC

Farming practices in Ancient Rome

500 BCE to 5th century CE. The Ancient Romans know about manure, fallowing, fertilising effects of leguminous plants, crop rotation and soil treatment with marl.

- 1200

Māori arrive in New Zealand

When Māori arrived in New Zealand they brought crops to cultivate.

- 1800

Māori and soil

Prior to the arrival of Europeans Māori had already identified at least 30 types of soil. Māori treated soils with ash, gravel or sand. They also practiced fallowing.

- 1818

Calcareous manures

Edmund Ruffin, an American agriculturalist, presents a paper explaining how, by applying calcareous earth (marl or lime), the acidity of soil can be reduced.

- 1826

Birth of soil chemistry

During the mid to late 19th century German botanist Philip Carl Sprengel (1787–1859) debunks the ‘humus theory’ of plant nutrition and replaces it with the ‘soluble soil salts’ theory – soil salts serve as plant nutrients not humus.

- 1836

Nitrogen cycle

From 1836–1876, French chemist Jean Baptiste Boussingault works on tracing the path of nitrogen between living organisms and the physical environment. He demonstrates that plants do not absorb nitrogen from the air but from the soil in the form of nitrate.

- 1838

Law of the minimum

The law of the minimum principle developed by Carl Sprengel in 1828 is popularised by German chemist Justus von Liebig. It states that plant growth is controlled not by the total amount of resources available but by the one present in the least amount.

- 1843

Rothamsted Estate

English entrepreneur and scientist John Bennet Lawes, owner of Rothamsted Estate, appoints chemist Joseph Gibert as his scientific collaborator. Together, they lay the foundations of modern scientific agriculture and establish the principles of crop nutrition.

- 1862

Pedology

German Friedrich Albert Fallou coins the term ‘pedology’. In his book of 1862, Fallou recognises the soil as a natural body that needs to be studied. He introduces the concept of soil profile and establishes a soil classification based on parent rock.

- 1880

Inception of soil science

Dokuchaev, Public domain

From mid to late 19th century German-American Eugene Hilgard (1833–1916) and Russian Vasily Dokuchaev (1846–1903) are key players in formalising the study of soil for the benefit of both farmers and the consumers of farm products. Dokuchaev sees the soil as “an independent natural-historical body” resulting from the collective influence of subsoils, climate, flora and fauna, geological age and relief of the locality.

- 1881

Darwin’s earthworm study

Charles Darwin’s book on earthworms is the first scholarly treatment of soil-forming processes.

- 1883

Dokuchaev and the Russian influence

Dokuchaev’s book on soil formation leads to his elevation as the founder of pedology by Russian soil scientists. Dokuchaev sees the soil as “an independent natural-historical body” resulting from the collective influence of subsoils, climate, flora and fauna, geological age and relief of the locality.

- 1885

Legumes and nitrogen fixation

Jim Deacon, Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Edinburgh

Germans Hermann Hellriegel and Hermann Wilfarth conduct experiments in nitrogen fixation in legumes. They establish that nodules on the legume root and the bacteria contained within allow the conversion of nitrogen from the air into compounds the plant can use.

- 1906

Influential book on soil science

The ‘father of American soil science’, Eugene Woldemar Hilgard, publishes a book that at the time becomes soil scientists’ standard text – Soils, their formation, properties, composition, and relations to climate and plant growth in the humid and arid regions.

- 1908

Glinka and pedogenesis

Russian Konstantin Glinka (1867–1927) contributes a great deal to the understanding of the principles of the geographical distribution of soils and soil formation. Glinka’s propagation of the principles of pedogenesis in Russia and abroad has a progressive influence.

- 1913

Haber-Bosch process

Germans Fritz Haber (1868–1934) and Carl Bosch (1874–1940) manufacture ammonia on an industrial scale. The Haber-Bosch process converts atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia. Nitrogen fertiliser generated from this process currently feeds an estimated one-third of the Earth’s population (2014).

- 1916

Born in England

Thomas William Walker is born on 2 July 1916 in Shepshed, Leicestershire, England.

- 1920

Soil classification

During the early 20th century Curtis F Marbut (1863–1935) develops the first formal soil classification scheme for the United States – classification of soils should be based on morphology instead of on theories of soil genesis. In 1911, Marbut publishes some of the first soil maps of the rich agricultural lands of the mid-western states such as Illinois.

- 1927

Educated at Loughborough Grammar School

Thomas is greatly influenced by his chemistry teacher Freddy Grey. Of the six fellow students in the upper 6th science class taught by Grey, five go on to graduate PhD and two became Fellows of the Royal Society.

- 1933

New Zealand Soil Bureau’s first pedologists

New Zealand Soil Bureau’s first pedologists, Dr Leslie Grange and Dr Norman Hargraves Taylor appointed. An English translation of Russian Konstantin Glinka’s book was published by American Curtis Marbutt. Marbutt’s translation has a significant impact on the early days of soil science in New Zealand and is the key text available in the 1930’s for the Soil Bureau.

- 1935

Cobalt deficiencies and sickness

Soil chemist Elsa Kidson and colleagues determine a lack of cobalt in soil is the cause of a serious wasting disease in cattle and sheep. They recommend adding small amounts of cobalt to the soil rather than feeding it to stock.

- 1935

Royal College of Science London, BSc

Awarded a Royal Scholarship. Graduates in 1937 with a BSc First Class Honours and as an Associate of the Royal College of Science

- 1939

Alternative forms of phosphate fertiliser

Thomas William Walker, as part of the Second World War effort in the UK, investigates alternative forms of phosphate fertiliser at Rothamsted Experimental Station, one of the oldest agricultural research institutions in the world.

- 1939

Royal College of Science London, PhD

Awarded the Diploma of Imperial College as well as a PhD in Agricultural Chemistry. The title of Walker’s thesis is The influence of soil type on the growth of plants.

1939Rothamsted Experimental Station

Jack Hill, Creative Commons 2.0

Receives a Salter’s Scholarship for 2 years to work at Rothamsted Experimental Station. Along with former Loughborough Grammar School classmate George Cook, they are given the task of finding alternative sources of phosphate fertiliser as back-up due to the prospect of the loss of the Pacific resources with the onset of the Second World War.

- 1941

Soil formation

In the mid to late 19th century, Swiss-American Hans Jenny (1899–1992), an expert on soil formation, devises a generic mathematical relationship that connects the observed properties of soil with the independent factors that determine the process of soil formation: S = f(cl, o, r, p, t, ...), where S is soil properties, cl is regional climate, o is potential biota, r is relief, p is parent material, t is time and any other identifiable variables.

- 1941

Factors of soil formation

Swiss-American Hans Jenny develops numerical functions to describe soil in terms of five interacting factors. In 1941, his seminal text Factors of soil formation is published. It is from this book that Thomas Walker draws inspiration, and most of his soil sequence studies are based on Jenny’s concepts.

- 1941

Manchester University

Appointed to the position of Lecturer and Adviser in Agricultural Chemistry. He spends the war years engaged in the British Government’s national food production programme applying his knowledge and research skills to boosting wartime food output – the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign.

- 1946

National Agricultural Advisory Service

Joins the NAAS as Provincial Advisory Soil Chemist in the West Midlands – the grassland region of England.

- 1952

Biological fixation by clovers

Irina Moskalev, licensed via 123RF Ltd

Between 1952 and 1958, Walker’s research group conducts a number of key field trials throughout Canterbury assessing the effects of phosphorus, nitrogen, molybdenum and sulfur on biological nitrogen fixation by clovers. From these studies comes a series of key papers leading to the greater understanding of legume nutrition.

- 1952

Canterbury Agricultural College, New Zealand

Courtesy of Lincoln University Archives, licensed under Creative Commons 3.0

Arrives in New Zealand with wife Edna and three daughters to take up an appointment as Foundation Professor of Soil Science. Canterbury Agricultural College is later named Lincoln College in 1961 and then Lincoln University in 1990.

1952Innovative soil fertility research

Courtesy Lincoln University

Begins ground-breaking research in adopting a soil sequence approach in field studies of soil fertility.

- 1958

King’s College, Newcastle upon Tyne

Returns to England to take up the Chair of Agriculture at King’s College, Newcastle upon Tyne, a college of the University of Durham, England.

- 1960

Soil sequences

On returning to Lincoln in 1960, Walker embarks on soil sequence studies over the following two decades, based on chronosequences, climosequences and lithosequences in both the South and North Islands, one of the first and most notable being the pedology of the Franz Josef chronosequence. These studies incorporate understanding from soil surveys into soil fertility by employing soil chemistry and mineralogy.

- 1960

Returns to Lincoln College

Returns to New Zealand to once again take up his original position as Chair of Soil Science at Lincoln College.

- 1976

Fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis

At Lincoln College (now University), studies of soil sequences continue throughout the 1970s, and many of these studies are incorporated in the 1976 Geoderma paper by Walker and Keith Syers – The fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. The paper distils data from four New Zealand soil chronosequences to show that soil nutrients follow predictable but fundamentally different patterns during long-term ecosystem development.

- 1979

Thomas retires

After holding the Chair of Soil Science at Lincoln University for 27 years, Professor Walker retires.

- 1985

Changes in world fertiliser use

Between 1950 and 1988, world fertiliser use rises from 14 million to 144 million tons. Fertiliser use peaks in the US and some western European countries in the 1980s. Since 1985, there has been a ten-fold increase in nitrogen fertiliser use in New Zealand.

- 1990

Soils and human impact

During the 1990s there is a growing awareness among the science community that soils and land use play an important role in moderating all of the environmental impacts of human existence – nutrient cycling, biodiversity loss, climate change and water quality among others.

- 1991

Television career

Professor Walker commences a journey into television, starring as the vegetable gardening ‘Prof’ in the programme Maggie’s Garden Show. Several series of this programme run from 1991 to 2003.

- 2000

Receives ONZM

© Crown Copyright 2002–2005.

Professor Walker is appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit (ONZM).

- 2004

Digital soil maps

Soil mapping moves online. Landcare Research develops S-map Online, a digital soil map and national soils database. S-map can be applied at any scale from individual back gardens to regions. S-map provides maps on specific soil attributes to help land users fine-tune soil management processes.

- 2010

Dies in Christchurch

On 8 November, aged 94, Prof Walker dies. Family members say, “He was small in stature but larger than life and passionate about four things – his wife Edna, his work, his fishing and the soil – the soil in his own garden and the soils of New Zealand.”

- 2015

Soils and climate change

The 4 per 1000 Initiative is launched at the Paris Agreement on climate change. The initiative proposes an annual 0.4% increase in soil carbon sequestration to help offset CO2 emissions. This voluntary action will also help soil fertility and food security.

Transcript

Changing scientific ideas

Each specialised field of science has key ideas and ways of doing things. Over time, these ideas and techniques can be revised or replaced in the light of new research. Most changes to key science ideas are only accepted gradually, tested through research by many people.

Advances in science and technology

All scientists build their research and theories on the knowledge of earlier scientists, and their work will inform other scientists in the future. A scientist may publish hundreds of scientific reports, but only a few are mentioned here.

Biography

This part of the timeline outlines just a few events in the personal life of the featured person, some of which influenced their work as a scientist.

CHANGING SCIENTIFIC IDEAS

Farming practices in Ancient Rome – 500 BCE

500 BCE to 5th century CE. The Ancient Romans know about manure, fallowing, fertilising effects of leguminous plants, crop rotation and soil treatment with marl.

Image: Public domain

Māori arrive in New Zealand – 1200

When Māori arrived in New Zealand they brought crops to cultivate.

Māori and soil – 1800

Prior to the arrival of Europeans Māori had already identified at least 30 types of soil. Māori treated soils with ash, gravel or sand. They also practiced fallowing.

Birth of soil chemistry – 1826

During the mid to late 19th century German botanist Philipp Carl Sprengel (1785–1859) debunks the ‘humus theory’ of plant nutrition and replaces it with the ‘soluble soil salts’ theory – soil salts serve as plant nutrients not humus.

Nitrogen cycle – 1836

From 1836–1876, French chemist Jean Baptiste Boussingault (1801–1887) works on tracing the path of nitrogen between living organisms and the physical environment. He demonstrates that plants do not absorb nitrogen from the air but from the soil in the form of nitrate.

Law of the minimum – 1838

The law of the minimum principle developed by Carl Sprengel in 1828 is popularised by German chemist Justus von Liebig. It states that plant growth is controlled not by the total amount of resources available but by the one present in the least amount.

Image: Justus von Liebig. Public domain

Pedology – 1862

German Friedrich Albert Fallou coined the term ‘pedology’. In his book of 1862, Fallou recognises the soil as a natural body that needs to be studied. He introduces the concept of soil profile and establishes a soil classification based on parent rock.

Inception of soil science– 1880

From mid to late 19th century German-American Eugene Hilgard (1833–1916) and Russian Vasily Dokuchaev (1846–1903) are key players in formalising the study of soil for the benefit of both farmers and the consumers of farm products. Dokuchaev sees the soil as “an independent natural-historical body” resulting from the collective influence of subsoils, climate, flora and fauna, geological age and relief of the locality.

Image: Dokuchaev, Public domain

Legumes and nitrogen fixation – 1885

Germans Hermann Hellriegel and Hermann Wilfarth conduct experiments in nitrogen fixation in legumes. They establish that nodules on the legume root and the bacteria contained within allow the conversion of nitrogen from the air into compounds the plant can use.

Image: Jim Deacon, Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Edinburgh

Soil classification – 1920

During the early 20th century Curtis F Marbut (1863–1935) develops the first formal soil classification scheme for the United States – classification of soils should be based on morphology instead of on theories of soil genesis. In 1911, Marbut publishes some of the first soil maps of the rich agricultural lands of the mid-western states such as Illinois.

Soil formation – 1941

In the mid to late 19th century, Swiss-American Hans Jenny (1899–1992), an expert on soil formation, devises a generic mathematical relationship that connects the observed properties of soil with the independent factors that determine the process of soil formation: S = f(cl, o, r, p, t, ...) where S is soil properties, cl is regional climate, o is potential biota, r is relief (or topography), p is parent material, t is time and any other identifiable variables.

Soils and human impact – 1990s

During the 1990s there is a growing awareness among the science community that soils and land use play an important role in moderating all of the environmental impacts of human existence – nutrient cycling, biodiversity loss, climate change and water quality among others.

ADVANCES IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

Calcareous manures – 1818

Edmund Ruffin, an American agriculturalist, presents a paper explaining how, by applying calcareous earth (marl or lime), the acidity of soil can be reduced.

Image: ‘Edmund Ruffin’ by Billy Hathorn – Fort Sumter National Monument, Charleston, SC. Licensed under Creative Commons 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Rothamsted Estate – 1843

English entrepreneur and scientist John Bennet Lawes, owner of Rothamsted Estate, appoints chemist Joseph Gibert as his scientific collaborator. Together, they lay the foundations of modern scientific agriculture and established the principles of crop nutrition.

Darwin’s earthworm study – 1881

Charles Darwin’s book on earthworms is the first scholarly treatment of soil forming processes.

Image: Public domain

Dokuchaev and the Russian influence – 1883

Dokuchaev’s book on soil formation leads to his elevation as the founder of pedology by Russian soil scientists. Dokuchaev sees the soil as “an independent natural-historical body” resulting from the collective influence of subsoils, climate, flora and fauna, geological age and relief of the locality.

Influential book on soil science – 1906

The ‘father of American soil science’, Eugene Woldemar Hilgard, publishes a book that at the time becomes soil scientists’ standard text – Soils, their formation, properties, composition, and relations to climate and plant growth in the humid and arid regions.

Glinka and pedogenesis – 1908

Russian Konstantin Glinka (1867–1927) contributes a great deal to the understanding of the principles of the geographical distribution of soils and soil formation. Glinka’s propagation of the principles of pedogenesis in Russia and abroad has a progressive influence.

Haber-Bosch process – 1913

Germans Fritz Haber (1868–1934) and Carl Bosch (1874–1940) manufacture ammonia on an industrial scale. The Haber-Bosch process converts atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia. Nitrogen fertiliser generated from this process currently feeds an estimated one-third of the Earth’s population (2014).

Image: “Fritz Haber” by Unknown – this image was provided to Wikimedia Commons by the German Federal Archive (Deutsches Bundesarchiv) as part of a cooperation project. The German Federal Archive guarantees an authentic representation only using the originals (negative and/or positive), resp. the digitalization of the originals as provided by the Digital Image Archive.

New Zealand Soil Bureau’s first– 1933

New Zealand Soil Bureau’s first pedologists, Dr Leslie Grange and Dr Norman Hargraves Taylor appointed. An English translation of Russian Konstantin Glinka’s book was published by American Curtis Marbutt. Marbutt’s translation has a significant impact on the early days of soil science in New Zealand and is the key text available in the 1930’s for the Soil Bureau.

Cobalt deficiencies and sickness – 1935

Soil chemist Elsa Kidson and colleagues determine a lack of cobalt in soil is the cause of a serious wasting disease in cattle and sheep. They recommend adding small amounts of cobalt to the soil rather than feeding it to stock.

Alternative forms of phosphate fertiliser – 1939

Thomas William Walker, as part of the Second World War effort in the UK, investigates alternative forms of phosphate fertiliser at Rothamsted Experimental Station, one of the oldest agricultural research institutions in the world.

Factors of soil formation – 1941

Swiss-American Hans Jenny develops numerical functions to describe soil in terms of five interacting factors. In 1941, his seminal text Factors of soil formation is published. It is from this book that Thomas Walker draws inspiration, and most of his soil sequence studies are based on Jenny’s concepts.

Biological fixation by clovers – 1952

Between 1952 and 1958, Walker’s research group conducts a number of key field trials throughout Canterbury assessing the effects of phosphorus, nitrogen, molybdenum and sulfur on biological nitrogen fixation by clovers. From these studies comes a series of key papers leading to the greater understanding of legume nutrition.

Image: Irina Moskalev, licensed via 123RF Ltd.

Soil sequences – 1960

On returning to Lincoln in 1960, Walker embarks on soil sequence studies over the following two decades, based on chronosequences, climosequences and lithosequences in both the South and North Islands, one of the first and most notable being the pedology of the Franz Josef chronosequence. These studies incorporate understanding from soil surveys into soil fertility by employing soil chemistry and mineralogy.

Fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis – 1976

At Lincoln College (now University) studies of soil sequences continue throughout the 1970s, and many of these studies are incorporated in the 1976 Geoderma paper by Walker and Keith Syers – The fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. The paper distils data from four New Zealand soil chronosequences to show that soil nutrients follow predictable but fundamentally different patterns during long-term ecosystem development.

Changes in world fertiliser use – 1980s

Between 1950 and 1988, world fertiliser use rises from 14 million to 144 million tons. Fertiliser use peaks in the US and some western European countries in the 1980s. Since 1985, there has been a ten-fold increase in nitrogen fertiliser use in New Zealand.

Digital soil maps – 2000s

Soil mapping moves online. Landcare Research develops S-map Online, a digital soil map and national soils database. S-map can be applied at any scale from individual back gardens to regions. S-map provides maps on specific soil attributes to help land users fine-tune soil management processes.

Soils and climate change – 2015

The 4 per 1000 Initiative is launched at the Paris Agreement on climate change. The initiative proposes an annual 0.4% increase in soil carbon sequestration to help offset CO2 emissions. This voluntary action will also help soil fertility and food security.

BIOGRAPHY

Born in England – 1916

Thomas William Walker is born on 2 July 1916 in Shepshed, Leicestershire, England.

Educated at Loughborough Grammar School – 1927

Thomas is greatly influenced by his chemistry teacher Freddy Grey. Of the six fellow students in the upper 6th science class taught by Grey, five go on to graduate PhD and two became Fellows of the Royal Society.

Royal College of Science London, BSc – 1935–37

Awarded a Royal Scholarship. Graduates with a BSc First Class Honours and as an Associate of the Royal College of Science.

Royal College of Science London, PhD – 1939

Awarded the Diploma of Imperial College as well as a PhD in Agricultural Chemistry. The title of Walker’s thesis is The influence of soil type on the growth of plants.

Rothamsted Experimental Station – 1939

Awarded a Salter’s Scholarship for 2 years to work at Rothamsted Experimental Station. Along with former Loughborough Grammar School classmate George Cook, they are given the task of finding alternative sources of phosphate fertiliser as back-up due to the prospect of the loss of the Pacific resources with the onset of the Second World War.

Image: Jack Hill, Licenced under Creative Commons 2.0

Manchester University – 1941

Appointed to the position of Lecturer and Adviser in Agricultural Chemistry. He spends the war years engaged in the British Government’s national food production programme applying his knowledge and research skills to boosting wartime food output – the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign.

Image: Poster by Peter Fraser (1888–1950), from The National Archives (United Kingdom). Public Domain

National Agricultural Advisory Service – 1946

Joins the NAAS as Provincial Advisory Soil Chemist in the West Midlands – the grassland region of England.

Canterbury Agricultural College, New Zealand – 1952

Arrives in New Zealand with wife Edna and three daughters to take up an appointment as Foundation Professor of Soil Science. Canterbury Agricultural College is later named Lincoln College in 1961 and then Lincoln University in 1990.

Image: Courtesy of Lincoln University Archives

Ground-breaking research – 1952

Ground-breaking research in adopting a soil sequence approach in field studies of soil fertility.

Image: Courtesy Lincoln University

King’s College, Newcastle upon Tyne – 1958

Returns to England to take up the Chair of Agriculture at King’s College, Newcastle upon Tyne, a college of the University of Durham, England.

Returns to Lincoln College – 1960

Returns to New Zealand to once again take up his original position as Chair of Soil Science at Lincoln College.

Thomas retires – 1979

After holding the Chair of Soil Science at Lincoln University for 27 years, Professor Walker retires.

Television career – 1991

Professor Walker commences a journey into television, starring as the vegetable gardening ‘Prof’ in the programme Maggie’s Garden Show. Several series of this programme run from 1991 to 2003.

Receives ONZOM – 2000

Professor Walker is appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit.

Image: © Crown Copyright 2002–2005.

Dies in Christchurch – 2010

On 8 November, aged 94, Prof Walker dies in Christchurch. Family members say, “He was small in stature but larger than life and passionate about four things – his wife Edna, his work, his fishing and the soil – the soil in his own garden and the soils of New Zealand.”