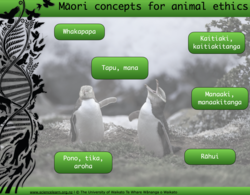

Tapu and mana are closely related foundational concepts in te ao Māori without which nothing else would exist.

Both tapu and mana are related to spiritual power since ngā atua are the source of both tapu and mana.

In te ao Māori, all animals have mana by virtue of being loved descendants of ngā atua and must therefore be treated with respect.

As ancient indigenous concepts, the full meaning of these concepts cannot be understood by equating them with English words since even using several English words or phrases in combination does not give a complete meaning in context. Tapu has long been equated to sacred or holy, and the meaning of mana is generally reduced to prestige or dignity.

Tapu is a dynamic state of heightened spiritual charge, which applies to life-and-death situations as it does to the space between hosts and guests in the formalities of a pōwhiri (welcome ceremony).

Another example of tapu is when people are warned to stay clear of a place if, for example, whakairo (carvings) are being erected until they have been made noa (opposite of tapu – unrestricted) through karakia and whakanoa ceremony.

In some situations, an animal such as a mokomoko (gecko/skink) is considered tapu because it is a representative or intermediary of ngā atua.

Tapu and mana are key concepts in Māori philosophy but do not work like scientific concepts because they are ethically loaded and because they do not equate to precise, stable definitions in the terms required by science.

Tapu is mentioned in relation to the death of animals as crossing the divide between ora (life) and mate (death) such as the planned euthanasia of laboratory animals as in Dr Kimiora Hēnare’s cancer research involving mice.

Tapu is also mentioned regarding the premature deaths of animals seen in natural populations – for example, high death rates of sea lion pups in their breeding colonies on Subantarctic Islands, which Ngāi Tahu observers describe to Rauhina Scott-Fyfe in their sea lion research.

Mana is also frequently mentioned by the researchers – noting every animal has its own mana and thus deserves to be treated with respect, including animals being used for food. For example, Hilton Collier recalls growing up on his family’s farm when an animal ‘for the house’ (selected to fill the freezer and provide a season of meals for the farm family) would be gently walked into the killing house. The animal would be rested and watered then dispatched and dressed. Everything contributed to the meat being tasty and tender and the experience of having looked after the animal from birth through to fulfilling its purpose as food.

In contrast, Hilton explains, when tired animals are loaded hurriedly onto a truck in hot conditions, they arrive at the meatworks stressed with elevated glycogen levels. The meat will not set properly and the resulting steak will not be tender but chewy, dark-coloured and terrible. If an animal is respected, its meat could be presented in premium quality and the farmer would be justified in expecting consumers to pay a premium because they can guarantee that steak will be consistently tender.

Even in the business of food production, it is important to remember that all living things have mana, and if treated as such, they end up providing a much better food experience.

Image: Wellington green gecko by Rod Morris, Department of Conservation.