Wayfinder navigators always look for signs of weather at sunrise and sunset. This is when they try to predict the weather for the next 12 hours.

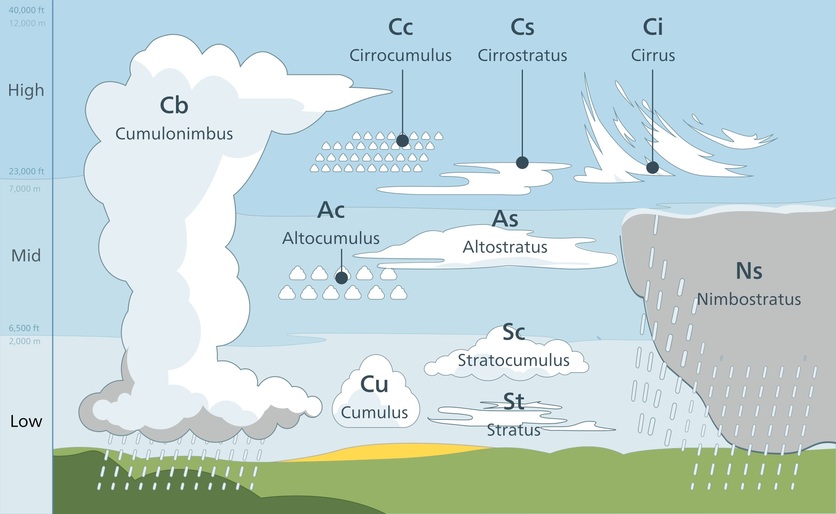

One of the easiest ways to predict weather is to look at the clouds. There are many different types of clouds in the troposphere (where all weather forms). Different clouds mean different types of weather.

Cloud names that describe the shapes of clouds are:

- cirrus – meaning curl (as in a lock of hair) or fringe

- cumulus – meaning heap or pile

- stratus – meaning spread over an area or layer.

Nimbus means rain-bearing, and alto means high. The following are some of the more common clouds used to predict weather in three categories – high-level, mid-level and low-level clouds.

High-level clouds

The bases of these clouds form at about 6200 metres above sea level. They are usually composed of ice crystals.

- Cirrus clouds – thin, wispy clouds strewn across the sky in high winds. A few cirrus clouds may indicate fair weather, but increasing cover indicates a change of weather (an approaching warm front) will occur within 24 hours. These are the most abundant of all high-level clouds.

- Cirrocumulus – like ripples or fish scales (sometimes called a mackerel sky). When cirrus clouds turn into cirrocumulus, a storm may come – in tropical regions, that could be a hurricane.

- Cirrostratus – like thin sheets that spread across the sky and give the sky a pale, whitish, translucent appearance. They often appear 12–24 hours before a rainstorm or snowstorm.

Mid-level clouds

The bases of these clouds form at about 2000–6200 m above sea level. They are mostly made of water droplets but can contain ice crystals. The clouds are often seen as bluish-grey sheets that cover most, if not all, of the sky. They can obscure the Sun.

- Altocumulus – composed of water droplets and appear as layers of grey, puffy, round, small clouds. Altocumulus clouds on a warm, humid morning may mean thunderstorms late in the afternoon.

Low-level clouds

The bases of these clouds form at altitudes below 2000 m. They are mostly made of drops of water.

- Cumulus – known as fair-weather clouds because they usually indicate fair, dry conditions. If there is precipitation, it is light. The clouds have a flattish base with rounded stacks or puffs on top. When the puffs look like cauliflower heads they’re called cumulus congestus or towering cumulus. They can get very high.

- Cumulonimbus clouds – thunder clouds that have built up from cumulus clouds. Their bases are often quite dark. These clouds can forecast some of the most extreme weather, including heavy rain, hail, snow, thunderstorms, tornadoes and hurricanes.

- Stratus – dull greyish clouds that stretch across and block the sky. They look like fog in the sky. Stratus cover is also called overcast. If their bases reach the ground, they become fog. They can produce drizzle or fine snow.

- Stratocumulus – low, puffy and grey, forming rows in the sky. They indicate dry weather if the temperature differences between night and day are slight. Precipitation is rare, but they can turn into nimbostratus clouds.

- Nimbostratus – dark grey, wet-looking cloudy layer so thick that it completely blocks out the Sun. They often produce precipitation in the form of rain and/or snow. Precipitation can be long lasting.

Cloud roads

Wayfinder navigators use clouds to work out where the wind is coming from or if it changes direction (so they can trim their sails accordingly). For example, they might look for cloud roads – puffs of cloud that come up from the far end of the horizon to form a ‘road’ in the sky. Like smoke from a haystack, cloud roads follow the wind. A cloud road indicates the wind is coming from the horizon. If the road is straight, the wind is steady – but if you see the road curve, it means that the wind direction will change. The way the road curves will tell you the new direction. Meteorologists call this kind of phenomenon ‘cloud streets’.

Examples of navigator weather talk

Navigators realise you can’t predict the weather from a single snapshot – that is, by noting how the sky looks at one moment in time. Instead, you have to observe changes over time.

Here are some examples of statements from navigator Nainoa Thompson concerning navigation and the weather (recorded by Sam Low during Hōkūle’a’s voyage from Tahiti to Hawai’i in February 2000):

- “The sky where the Sun is rising is clear – there are no smoky clouds caused by strong winds stirring salt into the atmosphere – so the winds will be relatively light today.”

- “There’s a change from seeing squalls off the starboard side yesterday to a view of high towering cloud masses but no active squalls. The wind feels stronger than the day before, and I can see wavelets on the surface of the ocean. The wind is coming from the normal direction of SE trade winds. There are low-level cumulus clouds ahead. No indications of squalls – approaching an area of clean-flowing wind from SE, which will be steady. Predict that, in the next 12 hours, the wind will remain steady from the SE at a fairly constant speed, maybe 10 knots, so we will be able to sail north today.”

Related content

The Connected article Sun, wind or rain? covers weather prediction.

Activity ideas

Clouds and the weather observes cloud types and how they help predict the weather.

Precipitation and cloud formation uses a slide show to help explain cloud and precipitation processes.

Useful links

Read the story of the Hōkūle’a and the beginnings of the wayfinding voyages of rediscovery. Explore the site for voyage tracking maps, learning journeys, videos, teaching activities and more related to the art and science of Polynesian voyaging.

Nephology, the study of clouds has always been a daydreamer’s science. It was founded by a young student who preferred to stare out the window rather than pay attention in class. This TED-Ed video explains how Luke Howard named and classified clouds.

Download a Clouds or wind poster from the MetService.