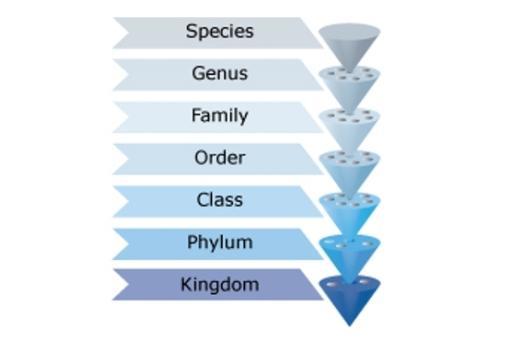

In the 18th century, Carl Linnaeus published a system for classifying living things, which has been developed into the modern classification system. People have always given names to things that they see, including plants and animals, but Linnaeus was the first scientist to develop a hierarchal naming structure that conveyed information both about what the species was (its name) and also its closest relatives. The ability of the Linnean system to convey complex relationships to scientists throughout the world is why it has been so widely adopted.

Despite existing for hundreds of years, the science of classification — taxonomy — is far from dead. Classification of many species, old and new, continues to be hotly disputed as scientists find new information or interpret facts in new ways. Arguments are fierce and species do change names, but only after a wealth of information has been gathered to support such a big step. One of the new reasons why species are being re-evaluated is because of DNA analysis. Basic genetic analysis information can change our ideas of how closely two species are related and so their classification can change, but how does the whole system work?

Nature of science

Improved technologies have altered our understanding of the world. In astronomy, the invention of the telescope enabled astronomers to observe outer space and see what they hadn’t been able to see before, and biologists use the microscope to observe the unseen world. Now, DNA technology has allowed scientists to re-examine the relationships between organisms to refine the classification system.

Kingdom

When Linnaeus first described his system, he named only two kingdoms – animals and plants. Today, scientists think there are at least five kingdoms – animals, plants, fungi, protists (very simple organisms) and monera (bacteria). Some scientists now support the idea of a sixth kingdom – viruses – but this is being contested and argued around the world.

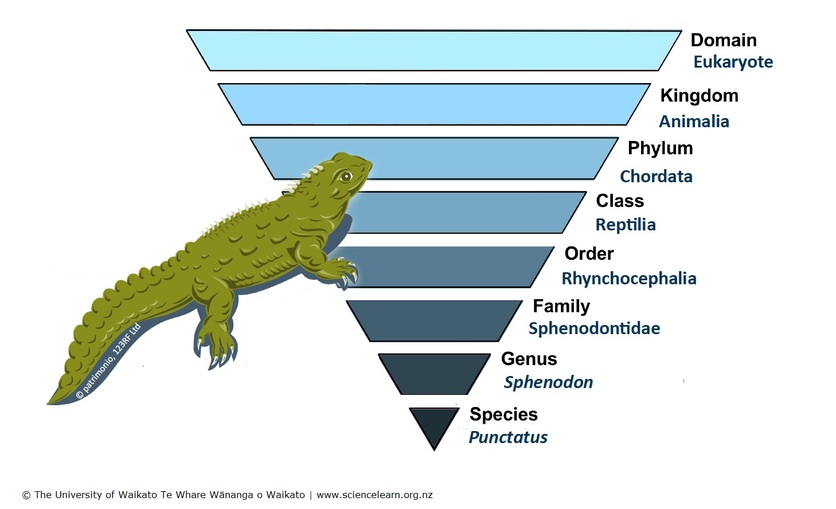

Phylum

Below the kingdom is the phylum (plural phyla). Within the animal kingdom, major phyla include chordata (animals with a backbone), arthropoda (includes insects) and mollusca (molluscs such as snails). Phyla have also been developed and reorganised since the original work by Linnaeus – as scientists discover more species, more categories and subcategories are put in place.

Class

Each phylum is then divided into classes. Classes within the chordata phylum include mammalia (mammals), reptilia (reptiles) and osteichthyes (fish), among others.

Order

The class will then be subdivided into an order. Within the class mammalia, examples of an order include cetacea (including whales and dolphins), carnivora (carnivores), primates (monkeys, apes and humans) and chiroptera (bats).

Family

From the order, the organism will be classified into a family. Within the order of primates, families include hominidae (great apes and humans), cercopithecidae (old world monkeys such as baboons) and hylobatidae (gibbons and lesser apes).

Genus and species

Finally, the classification will come to the genus (plural genera) and species. These are the names that are most commonly used to describe an organism. One outstanding feature of the Linnean classification system is that two names are generally sufficient to differentiate from one organism to the next. An example within the primate family is the genus Homo for all human species (for example, Homo sapiens) or Pongo for the genus of orangutan (for example, Pongo abelii for the Sumatran orangutan or Pongo pygmaeus for the Bornean orangutan).

Constant evolution

While this system of classification has existed for over 300 years, it is constantly evolving. Classification in the 1700s was based entirely on the morphological characteristics (what something looks like) of the organism. Those that looked most alike were put closest together in each category. This can be depicted as a tree, with the diverging branches showing how different the species become as you move out from the kingdoms (trunk).

Now, a radical shift in the grouping of organisms is occurring with the development of DNA technologies. Sequencing of the genetic code of an organism reveals a great deal of information about its similarity with and relationship to other organisms, and this classification often goes against the traditional morphological classification. Scientists are debating which species are most closely related and why.

Currently in New Zealand, there are projects to sequence kiwi and tuatara DNA that may revolutionise the way we think about these species and their closest living relatives. However, DNA technology is still expensive and time-consuming, so the first step in any classification continues to rely on a comparison of morphological features, similar to the process that Linnaeus undertook in the 1700s.

Activity idea

Your students can learn more about how the Linnaean classification system works with this activity, Insect mihi. Students write a formal introduction for an insect species of their choice, including information about the insect’s relationship to other animals and also the land.

Find out more

The article Māori knowledge of animals explores animal groupings using frameworks of whakapapa. It includes the Māori knowledge of animals interactive and has links to six articles that feature specific animal groupings.

Classification is not a field that stays still and this means scientists and taxonomists sometimes have to reassess classifications. Learn more in Leon Perrie's thought provoking blog, Why do scientific names change?

Useful links

Access the New Zealand Threat Classification System (NZTCS) database here.

Learn more about the five kingdoms on the Biology Online website.